When Board Intelligence CEO Pippa Begg met Sir George Buckley, the former CEO of 3M, he borrowed from atomic physics to explain why some companies succeed and others fail.

“Every business is decaying, yours included,” he said. “The question is: are you doing enough to replace that dying core?”

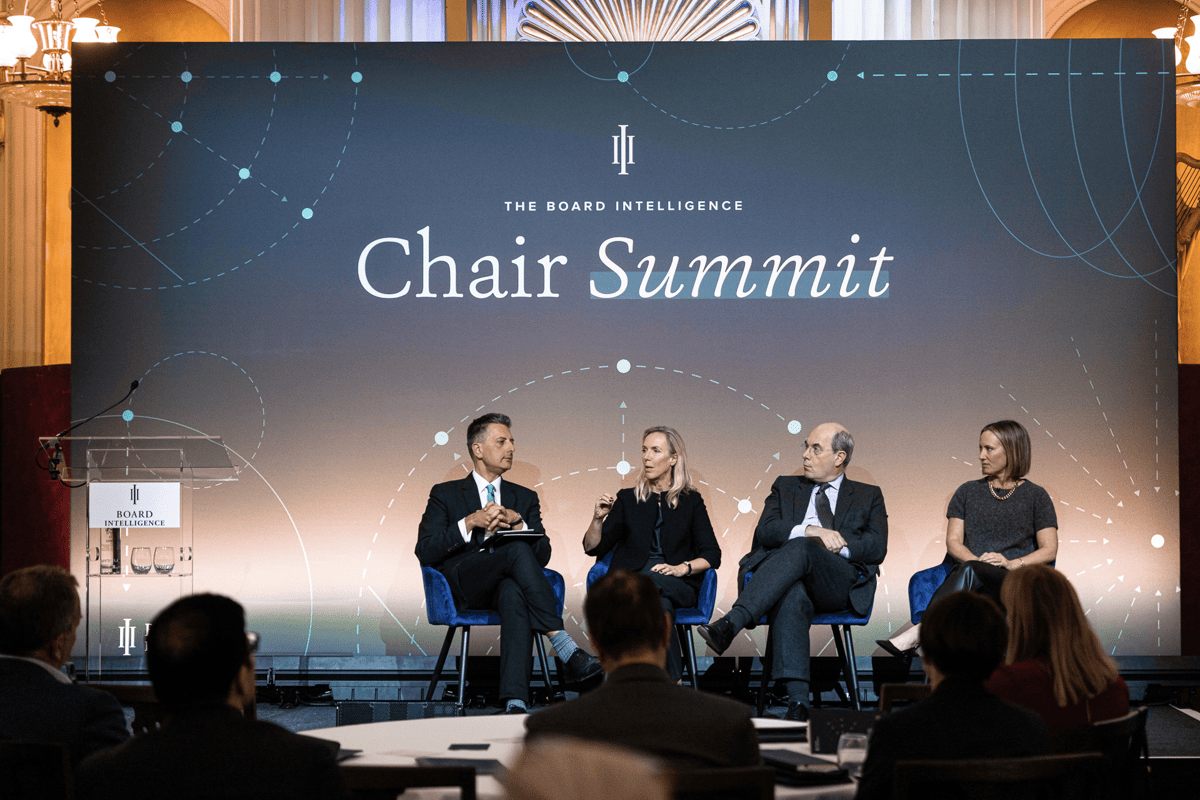

His message was simple: the businesses that succeed are the ones that innovate faster than they decay. That makes innovation the imperative of every leader — a reality acknowledged by most of the speakers at the Board Intelligence 2026 Chair Summit, an invite-only gathering of 200 chairs, CEOs, and senior directors from Europe’s leading organisations. The challenge for leaders today is that the rates of both decay and innovation are increasing because of AI and other emerging technologies.

Despite it being vitally important that boards lean into their innovation mandate, another thing we heard at the Summit was that boards – rather than being optimised for innovation – are optimised for something altogether different: risk management.

A panel of tech and blue-chip leaders at the Summit — including Google UK & Ireland MD Kate Alessi, Legal & General and Barclays UK chair Sir John Kingman, and Silicon Valley veteran and Board Intelligence chair Ann Hiatt — unpicked the issue and shared their perspectives on how boards can get it right.

Support an innovation culture

“The board needs to make sure it is not part of the problem.”

It may not be obvious to an outsider how a quarterly board meeting could materially affect the pace and quality of innovation in a business. But an organisation's ability to innovate is hardly independent of its governance.

Innovation inherently involves risk — placing bets on new products, markets, or ways of working. If the incentives and signals from the board are to take fewer risks or avoid making mistakes — to place fewer bets or only back dead certs — then that is ultimately what management will do.

It isn’t necessarily a question of simply taking more risks. Rather, the most effective boards support a culture of taking intelligent risks, something the world’s most innovative companies have perfected over the years.

For example, when things move quickly and under high levels of uncertainty, it is better to test hypotheses quickly to get better insight into which direction to go.

“During rapid innovation, you need to shorten experimentation cycles, rather than making a decision once and running really fast towards it,” said Hiatt..

This requires management to be in its “novice zone”, willing to try and fail in order to learn — and it requires boards to be willing to let them.

Build pro-innovation structures

Such hypothesis-driven experimentation won’t happen automatically, even with a supportive board. It also needs the right structures to encourage people to do it consistently throughout the organisation, and to nudge them when they don’t.

One example shared by our panel was drawn from a well-known tech firm, which requires senior management to run and report on three experiments every quarter. “A test-and-learn culture has to be top down… culturally you're setting the tone and metrics to make sure people actually do that work,” they observed.

Hiatt also talked about evolving the structure for decision making as the organisation grows, with Bezos instituting what he called "single-threaded leadership" to prevent a proliferation of approvals, meetings, and CC lines from slowing the pace of experimentation and, ultimately, action.

Set clear expectations for stakeholders

The board plays a vital role in communicating the value creation virtues of a more agile, innovation-first business to stakeholders — particularly investors.

Many will see the performance of the most innovative companies and actively want to understand how their business compares — and how it intends to keep pace. Some quick results can help to win them over, for example by addressing the “enormous amount of low hanging fruit in established organisations that technology can just do better,” as one speaker acknowledged.

It’s also important for boards to set clear expectations around exactly what innovation is solving for, especially when payback horizons may vary from what stakeholders are used to.

As Hiatt noted, “there are now business courses designed entirely around dissecting the shareholder letters Jeff Bezos wrote every year because in those he set the expectation: don’t invest in Amazon if you’re not here for the long term”.

Larry Page’s first CEO letter after Google’s IPO achieved something similar in setting out Google’s innovation stall: “Google is not a conventional company, and we do not intend to become one.”

Alongside this, it helps to give shareholders — and staff — an equally clear sense of what is not going to change. This will keep the organisation grounded and establish parameters to guide its innovation.

The innovation imperative

One of the key takeaways from the Chair Summit was that, as long-term stewards of the company, it is ultimately the board that needs to respond to Sir George Buckley's question about decay and innovation.

To do so, the board first needs to ask itself some hard questions — not just in regular board and director evaluations, but also in post-meeting reflections and post-decision retrospectives. Is the board prioritising its role in value creation and innovation as well as risk management? Is it looking ahead rather than backwards? Is it actively seeking forward-looking information and external insights? Does this reflect in how agendas are planned and board meeting time allocated? Is it visible in its board development programmes and in the criteria used to make non-executive appointments?

After all, it is only by getting itself fit for a changing world that the board can truly support its business to do the same — and ensure that, in the long-run, its rate of innovation can outpace its rate of decay.

Work with Board Intelligence’s team of board effectiveness experts to set your board up to succeed.

Find out more